Trust the government in Washington to do what's right ?

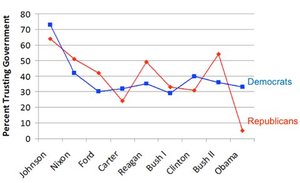

The American National Election Study has long included a question about how much people "trust the government in Washington to do what's right," with the possible answers being "just about always," "most of the time," or "only some of the time." In the third graph we plot the responses to this question from 1964 on, when the A.N.E.S. first started to ask the question regularly. The graph shows three major features.

The graph shows that Republicans don't trust government less than Democrats do, historically. The real difference is that Republicans are more sensitive to who controls the White House. When their man is in, they trust government more than Democrats do. When their man is out, they trust it less. Democrats hold steadier; they seem to identify "government" less with the presidency than Republicans do.

Jonathan Haidt is a professor of business ethics at the NYU-Stern School of Business and the author of "The Righteous Mind." Marc J. Hetherington is a professor of political science at Vanderbilt University and the author of "Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics." They both write for Civil Politics.org.

First, the long term trend is down. Way down. During the Johnson years, more than two-thirds of Americans said they trusted the government either just about always or most of the time. After Watergate and the Vietnam War, it dropped down closer to one third.

Reason for hope is that there are many changes we can make now, over the next few years, that might roll back the polarization by a decade or two. Several recent books contain lists of great ideas backed up by years of insider experience (see in particular Thomas Mann and Norm Ornstein's "It's Even Worse Than It Looks" and Mickey Edwards's "The Parties Versus The People"; see also the list from NoLabels.org). Some of these changes would reduce gridlock directly by making it easier for the majority party to implement its program - and then be held accountable by the public for the results. For example: making it harder to launch and sustain a filibuster in the Senate, or making it easier for a president to obtain a quick up-or-down vote on nominations for judicial and administrative appointments.