On Time

Few Northern Europeans or North Americans can reconcile themselves to the multi-active use of time. Germans and Swiss, unless they reach an understanding of the underlying psychology, will be driven to distraction. Germans see compartmentalization of programs, schedules, procedures and production as the surest route to efficiency. The Swiss, even more time and regulation dominated, have made precision a national symbol. This applies to their watch industry, their optical instruments, their pharmaceutical products, their banking. Planes, buses and trains leave on the dot. Accordingly, everything can be exactly calculated and predicted.

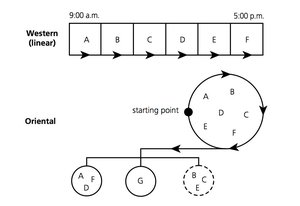

In countries inhabited by linear-active people, time is clock- and calendar- related, segmented in an abstract manner for our convenience, measurement, and disposal. In multi-active cultures like the Arab and Latin spheres, time is event- or personality-related, a subjective commodity which can be manipulated, molded, stretched, or dispensed with, irrespective of what the clock says.

The Japanese have a keen sense of the unfolding or unwrapping of time -- this is well described by Joy Hendry in her book Wrapping Culture. People familiar with Japan are well aware of the contrast between the breakneck pace maintained by the Japanese factory worker on the one hand, and the unhurried contemplation to be observed in Japanese gardens or the agonizingly slow tempo of a Noh play on the other.

What Hendry emphasizes, however, is the meticulous, resolute manner in which the Japanese segment time. This segmentation does not follow the American or German pattern, where tasks are assigned in a logical sequence aimed at maximum efficiency and speed in implementation. The Japanese are more concerned not with how long something takes to happen, but with how time is divided up in the interests of properness, courtesy and tradition.

Other events that require not only clearly defined beginnings and endings but also unambiguous phase-switching signals are the tea ceremony, New Year routines, annual cleaning of the house, cherry blossom viewing, spring "offensives" (strikes), midsummer festivities, gift-giving routines, company picnics, sake-drinking sessions, even the peripheral rituals surrounding judo, karate and kendo sessions. A Japanese person cannot enter any of the above activities in the casual, direct manner a Westerner might adopt.

The American or Northern European has a natural tendency to make a quick approach to the heart of things. The Japanese, in direct contrast, must experience an unfolding or unwrapping of the significant phases of the event. It has to do with Asian indirectness, but in Japan it also involves love of compartmentalization of procedure, of tradition, of the beauty of ritual.

For more, see the works of linguist and cross-culture studies expert Richard Lewis. Read "When Cultures Collide" and more at Richard Lewis Communications.